Github Method Search

This was a final project for the DD2476 Search Engines and Info Retrieval course at KTH Royal Institute of Technology during the spring 2020 semester while I was studying abroad.

Authors:

Levi Villarreal - villarreallevi@utexas.edu

Veronika Cucorova

Badr Ouannas

Abstract

While general search has become part of many people’s day to day life over the past few years due to its usefulness and versatility, there still does not exist a satisfactory solution for many programmers. Programmers often write pieces of code that could be easily re-purposed from existing projects, if they can find it. This project makes the use of GitHub’s API to index more than 72,000 methods using Elastic Search to build a code search engine. Compared to the GitHub code search tool, it allows for more restrictive filtering of the results and to search directly for method or class names. Ourvaluation shows that it can return relevant results for methods with well-known standardized names as well as queries aimed at finding out how to achieve the desired result with code.

Video demo of the project in action

Introduction

With a large amount of code being saved on code-hosting websites every day, and the explosion of much open-source software and public code repositories, the need for a flexi- ble, fast, and user-friendly code search engine has risen exponentially. With such a search engine a user can navigate a large amount of data and quickly filter out results that do not match their needs. Early successful search engines such as Google were notable because they were able to return meaningful results to the user quickly and consistently. While still popular today, those kinds of search engines are not quite as well suited for a user looking to navigate data sets of code. A programmer or an engineer would benefit from a search engine that takes into account code structure and can return a relevant method or class with the desired properties. Today, advanced search engine techniques are not just limited to large corporations such as Google, open search solutions allow for more niche, but still effective search engines to be created without much knowledge of information retrieval.

Background

In recent years, GitHub has implemented searching its codebase of over 100 million repositories[1]. While the search functionality has many different advanced features, itdoes not yet support searching via many of the aspects of the code itself. The search options and filters are currently limited to repositories options, issues options, user op- tions, and a small subset of these preferences left for code options. These options include searching for specific file extensions, code language, file size, pathname, and file name. However, these are not the only important aspects of code that a user might be inclined to search for. By narrowing down the scope to a specific programming language (in this case, Java), the search options can be much more specific than the ones currently offered by GitHub.

Related Work

The usefulness of a source code retrieval tool for developers is straightforward, but design- ing a tool that fully satisfies all code search needs is still an open problem today. However, there have been multiple attempts to construct a useful code search engine (CSE).

Existing Solutions

One of the earliest and largest attempts to solve this problem was Google Code Search, a tool built in 2006 that was shut down in 2012.[2] Another tool released in 2006 and still in use today is Krugle.[3] Krugle allows for advanced code search but has a relatively small codebase of projects to search through and currently primarily focuses on enterprise solutions. Black Duck Open Hub, formerly Ohloh, allowed users to search over 21 billion lines of code until it was discontinued in 2016. One of the largest CSE’s besides GitHub that still functions until today is SearchCode[4], which was launched in 2010. GitHub’s current search engine popularity is largely because before GitHub attempted to build any kind of CSE, they already had a massive codebase. Their API allows detailed searching for code and repositories but it lacks many of the functionalities offered by most of other CSE, such as syntax awareness features and support for regular expressions. A tool that aims to cover the shortcomings of GitHub search was constructed by Diamantopoulos and Symeonidis [5]. The tool allows for advanced search and fulfills all of the criteria that the authors listed as necessary for a functional CSE: syntax awareness, regular expressions, snippet search, project search, integration with hosting websites, and public APIs.

Current Research

A substantial part of the current research on CSE focus on improving the relevance of results, which is often unsatisfactory. This is partially caused by the lack of understanding of the user query because the search engine fails to grasp the intended function of the code that a developer is searching for. Fei et al.[6] built CodeHow, a tool that attempts to understand potential APIs related to the user query before performing the code retrieval. They crawled 26K repositories, resulting in 11.4 million methods written in C# that were subsequently indexed into elastic search. The API enriched version achieved significantly better results than a version omitting the API enrichment. Authors conclude precision equal to 0.794 when valued at the first result of CodeHow (i.e., 79.4% of the first returned results are relevant). Sachdev et al.[7] attempt to construct a search engine, which would accept natural language as its input, allowing developers to search by describing the intended operation.

Methodology

The methodology of the project consists of two main parts: information retrieval and the search engine. The information retrieval consists of the crawler, the parser, and the indexer. We found that using Python would be the most effective way to do this since it has a rich collection of libraries that help when filtering and collecting data. For the search engine, we aimed to create a web application, and given that the elastic search provides a RESTful API, we utilized Javascript which is commonly used with REST APIs and web applications. In the following sections, we will highlight how everything works starting from the crawling of GitHub to running the search engine.

Crawler

For this project it was necessary to gather source code data from GitHub. Naturally, the aforementioned GitHub search API became the backbone of the solution. While it was not our goal to access and download all of the public repositories available, we aim to access as many as possible providing users of our tool with the widest possible selection of potentially relevant methods. While directly accessing the API was a possibility that was considered, eventually, it was decided to use an ”intermediary” library PyGithub, which made downloading the contents more convenient, although the functionality is not much different from that provided by GitHub’s API.

The pipeline consisted of primarily two types of queries: searching for repositories(getting a list of the public ones) and requesting their content(navigating and downloading those that were written in Java). There were several constraints imposed by the design of the API. While the limits for a non-authenticated user are much lower, one can easily generate a token or use the com- bination of username and a password to access the API with much friendlier limitations, which we will describe further. There are three types of limits that constrain the API access:

- Search rate limit: Maximum of 30 search-repositories requests per hour per user.

- Core rate limit: Maximum of 5000 non-search related requests per hour per user.

- Maximum number of returned items: Maximum of 1000 that the search-repositories request returns at a time.

While the first limitation did not cause any issues, the other two presented bottlenecks. Core rate limit of 5000 needed to be spent not only on downloading the actual java files, but also traversing through the directories in the repositories and filtering out contents that were not java files. With this limit, we were still able to download several hundreds of java files per hour and then simply waited for the rate limit to renew.

The maximum number of returned items was solved using the idea of Van Gulick [8], who proposed using a date range when searching for repositories. This allows the query to be sliced and only request repositories created in a certain time range where the amount is preferably less than the limit of 1000, but not too much less to not make the query too fine-grained and waste the search rate limit. This allows the crawling to restart from a different time range that was not accessed yet to avoid crawling the same repositories again. With this method, we were able to crawl 13,493 java files.

Parser and Indexer

Since we chose to work with Java, we were able to index our search engine based on many attributes and options. Java, unlike many programming languages, uses a clear representation for its variables and methods, Python, for example, lacks the clarity that Java provides. Function definitions in Python don’t provide additional information about the function, other than its name. Looking at the source file only, one does not know the type of its parameters nor its return type. In Java, we can take advantage of its syntax rules to ”customize” our index. Along these lines, we used the library javalang library[9] which is written in Python.

After getting the Java files from the crawler, a parser which uses the javalang library[9], is used to filter out the methods in the files. The parser’s role is not only to find the methods but to also filter the important information about them, to construct an index for the search engine; The method’s names, its class, parameters and return type along with other information are stored in a dictionary which is stored in turn in a python list.

The list of dictionaries returned by the parser can then be used with the JSON library to turn it into a file usable by the search engine. We were able to parse 74,210 methods, divided into 17 files to ensure that each file contained a maximum of 5000 documents.

Elastic Search

Once the java files were converted to JSON, it allowed them to be easily used by the Elasticsearch[10] search engine. Elasticsearch allows a user to upload JSON documents, builds a search engine index, and provides a RESTful API that allows for easy implementa- tion in a web application. It handles fast and efficient document retrieval and implements document relevance scoring, multi-word queries, phrase queries, and many other features expected by a modern search engine. Furthermore, we used App Search[11] to provide refined APIs and a simple GUI that allowed us to view metrics and easily tweak search engine properties. With App Search, we adjusted relevance tuning to specify how much weight we gave to each document field, which allowed us to give more weight to a method name than we would the return type, for example.

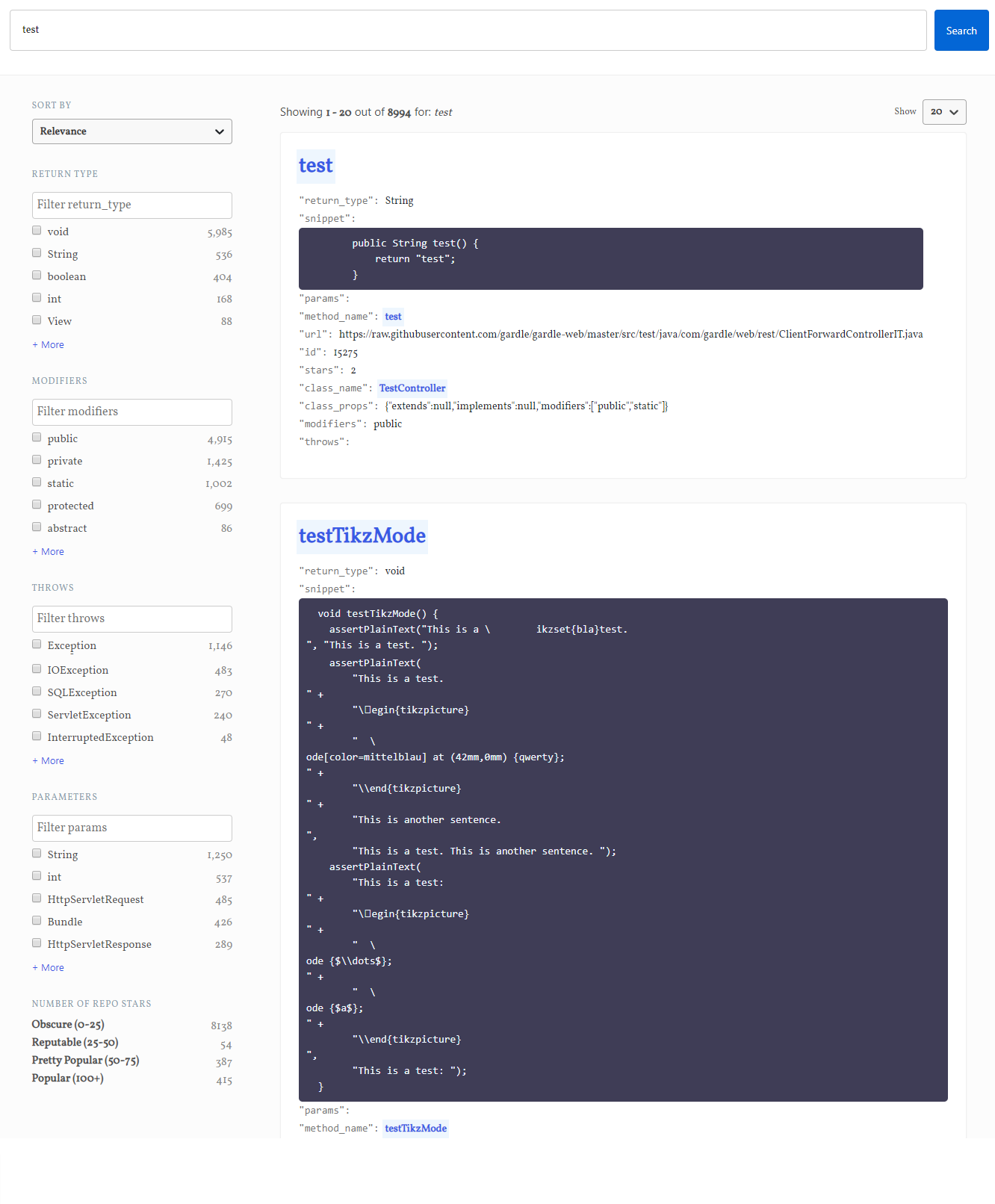

Web Search Interface

Using React[12] and Elasticsearch’s Search UI[13] allowed for quick integration of App Search’s APIs. Search UI allows us to build components and specify the format of the query, search results, and search filters. We were able to create filters for method return type, modifiers, exceptions, parameters, and the number of repository stars. These filters allow users to narrow down their search results to have the properties that they desire in the method they are searching for. Using Search UI, we also added different sorting options, which allowed users to sort the resulting methods by relevance, method name, or the number of repository stars. Furthermore, we were able to add in method name autocomplete, pagination, and custom styles to the web interface, which all made our search engine more robust and user-friendly.

The landing page of the search engine

The search interface

Evaluation and Results

In the following section we evaluated our search engine on two kinds of queries. The CSE users might look for an implementation of an algorithm that that is standard, such as ”Dijkstra’s algorithm”,where the method name is likely to be the same in all the instance of its implementation and is therefore easily searchable. A more common use case, however, is when a programmer searches for a way to achieve a certain result, eg. ”How to convert an integer to string?”. We aim to evaluate the search engine on both of these types of queries.

Retrieval of well-known methods

We evaluated the search engine on the returned results for three standard queries that search for implementations of a well-known standard algorithm or function. We evaluate each of these queries on precision, recall, and normalized cumulative gain at the 10th result. Two human judges were used to evaluate the relevance of given results using the following scale:

- 3 : if the result implements the requested algorithm

- 2 : if the result implements a similar algorithm

- 1: if the result calls the requested algorithm from somewhere else in the project or from an imported library

While evaluating the relevance of the results, the judges did not check the correctness of the method returned, simply inspected the implementation visually. The minimum of two judges’ independent evaluation was used as the relevance scoring for each result.

The tables show the result of our evaluation for three different queries. Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain which we refer to as NDCG is one way to evaluate a search engine for a certain query, especially when evaluating a search engine based on how well it ranks relevant results. Precision was calculated using any result relevance score above zero as relevant. As stated before, although the evaluation only used two judges, we can still make some conclusions about the search engine and its limitations. At first glance, we can see that the query euclidean distance did not give very good results in comparison to the other two queries. We assume that contrary to the other queries the code for this query is not uncommon and simple, which means it can be written in a single line of code without mentioning the name of the function making it less searchable. Another reason is that the query is very specific, a search engine replying to a query about euclidean distance would likely give many results about distance rather than the specific query, since it is a common word in methods. Precision for quicksort and hash was reasonably high when evaluated at 10. For both, the results contained methods with implementation from scratch and methods that called the algorithm from somewhere else. For hash functions, it is more common to not design a custom implementation and therefore even the usage of libraries in the solution was evaluated by the judges with the full relevance score.

Retrieval of real-world queries

In order to test how well the search engine performs in grasping the intent of the user, we took approach similar to Fei et al.[6] for evaluating CSE. Stack overflow provides a great source of mapping from real-world user queries to the answer or a snippet code the users were searching for. We selected two of the most popular questions asked on Stack Overflow related to Java. Despite the fact the original evaluation in CodeHow[6] aimed to see if the search engine can recognize the intent of the user asking the query even in natural language, we simply focused on such questions that ask for a snippet or exemplary implementation rather than explanation of how something works. We define relevant snippets using the same evaluation as in 5.1 where the top answer from Stack Overflow defines what is the requested algorithm.

Results for the query: ”Quicksort”:

| Relevance | CG | DCG | Ideal | ICG | IDCG | NDCG | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0.33333 | 1 |

| 2 | 3 | 1.89278 | 2 | 5 | 3.15464 | 0.6 | 1 |

| 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 0.66666 | 1 |

| 3 | 7 | 3.01473 | 1 | 7 | 3.01473 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 8 | 3.09482 | 1 | 8 | 3.09482 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 9 | 3.20586 | 1 | 9 | 3.20586 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 10 | 3.33333 | 1 | 10 | 3.33333 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 11 | 3.47011 | 1 | 11 | 3.47011 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 11 | 3.31132 | 0 | 11 | 3.31132 | 1 | 0.88888 |

| 0 | 11 | 3.17971 | 0 | 11 | 3.17971 | 1 | 0.8 |

Results for the query: ”Euclidean distance”:

| Relevance | CG | DCG | Ideal | ICG | IDCG | NDCG | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.26185 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.86135 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 2 | 0.77370 | 0 | 2 | 0.77370 | 1 | 0.2 |

| 0 | 2 | 0.71241 | 0 | 2 | 0.71241 | 1 | 0.16666 |

| 0 | 2 | 0.66666 | 0 | 2 | 0.66666 | 1 | 0.14285 |

| 0 | 2 | 0.63092 | 0 | 2 | 0.63092 | 1 | 0.125 |

| 0 | 2 | 0.60205 | 0 | 2 | 0.60205 | 1 | 0.11111 |

| 0 | 2 | 0.57812 | 0 | 2 | 0.57812 | 1 | 0.1 |

Results for the query: ”Hash”:

| Relevance | CG | DCG | Ideal | ICG | IDCG | NDCG | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 6 | 3.78557 | 3 | 6 | 3.78557 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 9 | 4.5 | 3 | 9 | 4.5 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 9 | 3.87608 | 3 | 12 | 5.16811 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| 0 | 9 | 3.48167 | 3 | 15 | 5.80279 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| 3 | 12 | 4.27448 | 3 | 18 | 6.41172 | 0.66666 | 0.66666 |

| 2 | 14 | 4.66666 | 2 | 20 | 6.66666 | 0.7 | 0.71428 |

| 3 | 17 | 5.36290 | 0 | 20 | 6.30929 | 0.85 | 0.75 |

| 3 | 20 | 6.02059 | 0 | 20 | 6.02059 | 1 | 0.77777 |

| 0 | 20 | 5.78129 | 0 | 20 | 5.78129 | 1 | 0.7 |

-

How do I generate random integers within a specific range in Java?

URL: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/363681/how-do-i-generate-random-integers-within-a-specific-range-in-java

Our search query: “random integers range”

Expected result (the approved and most voted answer for this question):

import java.util.concurrent.ThreadLocalRandom; // nextInt is normally exclusive of the top value, // so add 1 to make it inclusive int randomNum = ThreadLocalRandom.current().nextInt(min, max + 1);Precision at 1: 1

Precision at 5: 0.4

Precision at 10: 0.4

-

How to split a string in Java

URL: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/3481828/how-to-split-a-string-in-java

Our search query: “split string”

Expected results (the approved and most voted answer for this question):

String string = "004-034556"; String[] parts = string.split("-");or

String[] parts = string.split(Pattern.quote("."));Precision at 1: 0

Precision at 5: 0.2

Precision at 10: 0.5

Despite the fact the search engine does not employ any natural language processing meth- ods and does not focus on understanding the user’s intended use of the function, for spe- cific queries it performs reasonably well. CodeHow’s precision results at 1, 5 and 10 were 28.5%, 72.8%, 78.3% respectively. Evaluated on the average of two selected queries our precision reaches 50%, 30%, and 45%.

Discussion and Conclusions

While the goals of the project were accomplished, naturally there is much room for im- provement and design decisions of our search engine that can be discussed. Firstly, one can easily notice that despite non-negligible amounts of data, the search engine is not able to return satisfying results for simple standard operations that are certainly implemented uncountable times if we were to search all of GitHub’s repositories, such as the query ”euclidean distance”. This indicates that a larger amount of data might be needed to serve the purpose properly.

Additionally, despite the non-negligible amount of data a lot of the methods in our index seem to be project-specific - their purpose is not clear and cannot be inferred from the method or class name. The design of our search engine is probably best suited for methods with well-known standard names. This links to the fact that a big part of CSE research nowadays focuses on recognizing the original intent of the user and retrieving code snip- pets that satisfy the intent even if their method name or class name does not directly describe the intent. In this way, the search engine would be much more user-friendly for the programmers.

The weight of different components for sorting the results could be better fine-tuned to the user’s needs. While currently, the biggest weight contribution is if a query term is present in the method or class name, the presence of the term in the code snippet is not very significant. The best weight ratio largely depends on the query and therefore a possible improvement would be giving the user freedom to set this ratio.

Naturally, it is desired to have the highest quality results returned first. Our search en- gines can use the number of stars the repository has as the measure of the quality of the methods in it. While this is a valuable indicator, it does not directly reflect whether the repositories are well maintained, employ the coding standard and best engineering practices, it might just reflect that many users saved this repository for later. As a future improvement, we suggest using a combination of various metadata of the repository to infer its reputability.

In conclusion, the search engine built is not perfect and has multiple possible areas of im- provement. It cannot compete with the industry and the standard GitHub API, mainly due to the significantly larger amount of searchable code on GitHub. However, it satisfies our original goal - to allow for the search through method and class names and allows for more flexibility for restricting the results with filters. It is deployed and freely accessible and greets its users with a clean and understandable interface. The precision of its results is reasonably good for the standard algorithms as well as the real-world queries.

REFERENCES

-

“Github advanced search.” https://github.com/search/advanced.

-

B. Horowitz, “A fall sweep.” https://googleblog.blogspot.com/2011/10/

fall-sweep.html.

-

“Krugle.” http://opensearch.krugle.org/.

-

“Searchcode.” https://searchcode.com/about/.

-

S. A. L. Diamantopoulos T., “Source code indexing for component reuse.,” in Mining Software Engineering Data for Software Reuse, (Thessaloniki, Greece), pp. 101–132, Springer, 2020. Available at http://agora.ee.auth.gr/.

-

F. Lv, H. Zhang, J.-g. Lou, S. Wang, D. Zhang, and J. Zhao, “Codehow: Effective code search based on api understanding and extended boolean model,” in Proceedings of the 30th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineer- ing, ASE ’15, p. 260–270, IEEE Press, 2015.

-

S. Sachdev, H. Li, S. Luan, S. Kim, K. Sen, and S. Chandra, “Retrieval on source code: A neural code search,” in Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGPLAN International Workshop on Machine Learning and Programming Languages, MAPL 2018, (New York, NY, USA), p. 31–41, Association for Computing Machinery, 2018.

-

D. van Gulick, “Crawling online repositories for openmp/openacc code,” (Amster- dam, Netherlands), University of Amsterdam, 2018. Available at https://esc. fnwi.uva.nl/thesis/centraal/files/f7174372.pdf.

-

c2nes, “Javalang library.” https://github.com/c2nes/javalang.

-

“Elasticsearch.” https://github.com/elastic/elasticsearch.

-

“App search.” https://www.elastic.co/app-search/.

-

“React.” https://reactjs.org/.

-

“Search ui.” https://github.com/elastic/search-ui.