Twitter Style Transfer

This was the final project for my grad-level course CS 395T - Topics in Natural Language Processing.

View our live demo to check out the project yourself!

Authors:

Levi Villarreal

Isaac Buitrago

Abstract

Recent works on style transfer have allowed for the re-creation of everyday images with stylistic features from other works, such as being able to recreate your headshot in the style of a Gauguin painting. However, little research has been done in applying this method to text. In this paper, we investigate existing Recurrent Neural Network-based architectures for performing style transfer on Twitter data. With an ultimate goal of being able to re-create arbitrary input text in the writing style of any desired twitter account (e.g. @garyvee), we also created a user interface to facilitate understanding and experimentation in this domain. Our codebase and model have been published to Github to encourage further work.

Introduction

Style Transfer is a domain that has seen tremendous progress in recent years, mainly due to breakthroughs in convolutional neural networks used in image transformation (Gatys et al., 2016). It has also greatly increased in popularity, with this particular domain becoming more visible and widely used by the public. One such example of image-based style transfer can be seen in AI Gahaku, a viral website that allows users to download user-provided images in the style of Renaissance paintings (Sato, 2020). This service exploded in popularity and allowed millions of users to explore the concept of style transfer in an easy to use and approachable way.

While this sort of mainstream popularity has been enjoyed in the field of image style transfer, style transfer for text has not yet had a comparable impact or interest both by researchers, and the general public. Recent work has focused on the problem of transferring a single style from one text to another, for example, a statement with a negative tone to a positive one (Tikhonov et al., 2019). However, research thus far has not proved accessible or even applicable to most people and lends itself primarily to specialized business applications.

One domain with the potential for more widespread use is Twitter. Twitter is a microblogging website with over 321 million active users that allows accounts to post 280 character messages called ”tweets”. This character limit, and the ability for users, including notable public figures, to broadcast immediately and directly to followers, makes Twitter a very unique source of author annotated text. On the platform, users can also create and interact with many bots on the platform, including some that perform image style transfer based on realtime transfer models (Johnson et al., 2016). Hence, we propose studying text-based style transfer between several notable Twitter accounts.

Previous work focuses almost entirely on sentiment transfer, and additionally, little attention has been given to Twitter as a source of data for such a task. Therefore we contribute,

- A dataset comprised of 294,911 labeled tweets from 26 Twitter accounts belonging to notable public figures. This public dataset fills a gap in previous work and allows for reproducibility and easier development of future work.

- A tweet generation model with controllable parameters.

- A web-based platform to allow for users to easily generate and share generated tweets. This application brings us closer to our original motivation to have such text-based style transfer models be more accessible and mainstream.

Related Works

Style Transfer for Text

Because the field of style transfer for text has not seen as much attention as other fields in natural language processing, there is little that is agreed upon among researchers (Tikhonov and Yamshchikov, 2018). This lies in stark contrast to image style transfer, which has more concrete definitions that increase the ease of research in the area. However, there are some prevailing themes seen in related work that give this study a starting point.

Although sentiment and style are not equivalent, many studies focus on sentiment specifically as an area of study within style transfer. For example, one of the most widely used benchmark in text style transfer is the Yelp Review Dataset, which is used to train models to convert between text with negative and positive sentiment (Tikhonov et al., 2019). However, this focuses on style transfer between two distinct sentiments and does not allow for an arbitrary number of styles.

Another common approach to text style transfer is to represent different styles as different languages. Neural machine translation is one of the most studied topics in natural language processing, so text style transfer research that utilizes translation can leverage a wider body of work. One such task that leverages this approach is converting modern-day English to Shakespearean English (Jhamtani et al., 2017). Because the Elizabethan style words and phrases of Shakespeare often have direct mappings to today’s English, it follows that a model can use similar techniques to neural machine translation to perform style transfer. However, this approach is often limited by the availability of parallel datasets and requires extensive human annotation for feasible results.

Work Involving Twitter Datasets

Twitter has long been used as a source of natural language processing data in many different topics. Twitter has both large amounts of user-generated text and the ability to search for topics through the use of ”hashtags”. Because of these factors, datasets have been compiled on topics ranging from gender discrimination (Burger et al., 2011) to COVID-19 (Chen et al., 2020). There has even been a sentiment analysis dataset compiled using Twitter (Saif et al., 2013). These studies use Twitter as a source for natural text generated by a diverse group of users. Unfortunately, this means that such datasets tend to include thousands if not millions of unique user accounts, with only a small number of tweets that are associated with each account. To our knowledge, we are the first to address this lack of data regarding individual high-profile twitter accounts.

Accessible NLP Interfaces

Natural language processing models are increasingly being used both to study aspects of social media and as part of the platforms themselves (Alvarado and Waern, 2018). This technology can often be out of reach to those who are affected by it, namely the non-technical experts who use social media. There is a growing body of work that seeks to facilitate greater accessibility of artificial intelligence breakthroughs by designing interfaces that are intuitive and have a low barrier of entry (Lee et al., 2019). We seek to embody this in our research by providing an accessible interface with which to utilize a model.

Dataset

As shown in Table 1, many existing Twitter datasets either capture tweets from a very large number of accounts or compile a corpus of tweets relating only to a specific topic. Furthermore, many previous works have not made their datasets public, which hinders attempts to reproduce results and conduct further research. Many times the datasets have been taken down by Twitter themselves due to the existence of identifying information of private individuals.

| Dataset | # Tweets | # Unique Accounts | Single Topic | Public |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | 294,911 | 26 | No | Yes |

| (Bin Tareaf, 2017) | 52,543 | 20 | No | Yes |

| (Wang et al., 2016) | 3,085 | 13 | Yes | Yes |

| (Yang and Leskovec, 2011) | 476,553,560 | 17,069,982 | No | No |

| (Burger et al., 2011b) | 4,102,434 | 183,729 | No | No |

Table 1: Statistics of various Twitter datasets used for NLP research.

To address these issues, we scrape our own dataset from notable public figures using Twitter’s search API. We compile a list of 26 public figures from across politics, music, etc., with large followings. This results in 294,911 tweets after all of the text is cleaned. This size is larger than other corpora used for the related task of sentiment transfer (Wang et al., 2016) and notably provides a reproducible framework to easily generate and clean tweets for any additional accounts.

Tweet Collection Overview

Once the accounts were selected, we used an open-source tool that utilizes Twitter’s search API to scrape tweets (ignoring retweets) from each individual account. The official Twitter API currently has a limit of the 3000 most recent tweets from any given account, so this tool allows us to bypass that restraint. We publish scripts to reproduce this data on our GitHub repository, along with the data itself, so that different accounts can be added with ease.

As seen in figure 1 and figure 2, there is a high variation in both the number of tweets available for each account, as well as the average length of each tweet. Despite these variations, we believe that this data is sufficient to train our model.

Figure 1: Graphical representation showing the number of tweets for each Twitter account retrieved.

Figure 2: Graphical representation showing the average tweet length for each Twitter account retrieved. Note that the Twitter character limit is currently 280, a change introduced in 2017 from the original limit of 140 characters (Rosen, 2017).

Tweet Cleaning Overview

While exploring the data, we found that certain accounts had many reply tweets - tweets that are direct replies to the tweet of another user. Furthermore, we found that many tweets contained nothing but a link to an image, video, or external website. We choose to remove both categories of tweets and also removed links entirely from the dataset. This resulted in 59,342 tweets being removed. Future versions of this dataset could include images or videos. This could extend our work to the language + image and language + image + speech domains, which would allow for both image and text style transfer among Twitter accounts.

Network Architecture

The network architecture was inspired from (Hu et al., 2017), where a variational auto-encoder (VAE) is trained to reproduce tweets conditioned on the latent space z and a configurable parameter c; There is a dimension in c for each Twitter account in our training set (total of 4 due to hardware constraints in processing additional data). Adversarial learning is then used to classify tweet attributes and compute the error of recovering the desired features in the latent space. The entire network was implemented in PyTorch, where tensorboard was utilized to evaluate learning curves and generated text. We modified an existing codebase (Hu et al. 2017) to perform controlled generation on Twitter data.

Figure 3: Network architecture - VAE model, where z is the latent space and c is the structured code that targets twitter attributes to control. The red dashes denote the cross entropy loss between a generated sentence and it’s original form and the loss between a classified twitter account its ground truth ”gold” label.

Generator Learning

The VAE is responsible for learning the latent space z, which is an underlying representation of the training data. It also learns how to reconstruct tweets conditioned on the latent space and a controllable parameter \(c\) (twitter account name):

\[G(z, c) = p*{G}(\hat{x} | z,c) = \prod*{t} p(\hat{x}\_t | \hat{x}^{t-1},z,c)\]Here, \(\hat x\) is the generated word at timestep t. Both the encoder and decoder are implemented as LSTM’s. The encoder takes in an embedding of a tweet and passes the hidden states to two linear layers to learn the mean and log-variance of the input.

\[E(x) = q\_{E}(z|x)\]Here \(x\) are the embeddings of the input tweet - embeddings are also learned during training.

The decoder (or generator) then generates a tweet given the input embeddings conditioned on prior gaussian distributions \(z\) and \(c\). A reconstruction error is computed between the original tweet and the generated tweet to improve the parameters of the VAE, while minimizing the KL-divergence between outputs of the encoder and the prior $ z $:

\[L*{\text{VAE}} = -KL(q*{E}(z|x) \|p(z)) + E\left[\log {p_{G}(x|z,c)} \right]\]This objective updates the parameters of the generator in the first step of training. Once the VAE has converged, the generator parameters are updated once again as a part of discriminator learning. In the second step of training, both the discriminator and encoder are used to update the generator’s parameters. At each timestep, the hidden state of the generator is fed through a linear layer to learn a discrete distribution over the word vocabulary. Given that this distribution is not differentiable, the logits of this layer are passed through softmax to create a probability distribution. These are known as ”soft” sentences, Gτ (z, c). These soft sentences are passed through the discriminator to measure the loss between the classified twitter account and the randomly sampled account c. The loss is defined as such:

\[L*{c}(\theta*{G}) = E\left[ \log_{q_{D}}{(c| \tilde{G_{\tau}}(z,c))}\right]\]This guides the generator to create tweets for a given account \(c\). Other attributes in the training data that are not directly accounted for in this project (e.g. tone) are captured by the latent code \(z\) . Thus, the encoder is trained to infer the latent code from the generated soft sentences:

\[L*{z}(\theta*{G}) = E\left[\log_{q_{E}}{(z | \tilde{G_{\tau}}(z,c))} \right]\]In this second step of training, the VAE loss is computed once again to obtain the generator objective:

\[min*{\theta*{G}} L*{G} = L*{VAE} + \lambda*{c} L*{c} + \lambda*{z} L*{z}\]Here \(\lambda_c\) and \(\lambda_z\) are balancing parameters set to 0.1 during training.

The VAE was trained for 600 epochs with an adaptive learning rate of .001 on a single NVIDIA 1080 GTX GPU using Adam optimization.

Figure 4: VAE training loss over 600 epochs

Figure 5: VAE training loss over 100 epochs

Discriminator Learning

While the VAE is trained in an unsupervised manner, labeled examples are used to learn a specific accounts’ writing style. For example, the generated tweet ”ignorance outraged actions” would be classified as belonging to @DalaiLama by the discriminator and then compared against the ground truth label. Equation 7 shows the objective used to learn the semantic relationship between generated tweets and it’s corresponding twitter account with labeled examples \(X_L = {(x_L, c_L)}\) (Hu et al., 2017). This is a supervised loss.

\[L*{s}(\theta*{D}) = E*{x_L} [\log*{q*{D}}(c*{L} | x\_{L})]\]The wake-sleep algorithm is used to augment training data. This is an unsupervised learning algorithm with two phases that adjust the parameters of a deep neural network to produce a good density estimator of the input. In the ”wake” phase, generative connections are adapted to increase the probability of reconstructing activation vectors in lower layers. In the ”sleep” phase, recognition connections are adapted to increase the probability of reproducing activation vectors in higher layers (Hinton et al., 1995). In this project, this was realized as tweets produced by a generator and classified by the discriminator. The cross-entropy between these classifications and the prior distribution for \(c\) were used as an unsupervised loss:

\[L*u(\theta*{D}) = E\left[ \log q_{D}(c|\hat{x}) + \beta \mathcal{H}(q_{D}(c'|\hat{x}))\right]\]The discriminator is trained in an semi-supervised fashion through a joint objective that learns from labeled samples and generated samples:

\[min*{\theta*{D}} L*{D} = L*{s} + \lambda*{u}L*{u}\]Here \(\lambda_u\) is a balancing parameter set to 0.1 in training. Because the discriminator classifies a generated tweet as originating from one of four twitter accounts, it is implemented as a sentence classifier with three stacked convolutional layers and is trained after the VAE (Kim, 2014).

The discriminator was trained for 100 epochs with a learning rate of .001.

Results

Although our original goal of performing style transfer on input text is a work in progress, we successfully developed a model capable of text generation conditioned on a users’ account. As seen in Table 7, three tweets generated for each account in our training set.

Evaluation

The main results of our study are in Table 2. For our baseline, we train a AWD LSTM model (Merity et al., 2017) with dropout (Srivastava et al., 2014). However, because no existing baseline allowed us to easily generate text for multiple styles, we instead trained the baseline model on the four different sets of Twitter data individually, resulting in four pre-trained models from which we evaluated predictions.

| Avg. Fluency | Style Similarity | Avg. Type Token Ratio | Avg. Sentiment Err | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | 1.34 | 2.22 | 0.6493 | 0.5888 |

| Baseline | 2.67 | 3.89 | 0.8243 | 0.1682 |

Table 2: Evaluation of our model and a baseline model across 200 generated tweets.

We list the scores for the human evaluation metrics of fluency, and style similarity, how likely the generated text is to be said by that account. The human evaluations were conducted by the researchers of this study on a scale of 1-5, 1 being incoherent/nonsense and 5 being indistinguishable from the human-generated text.

We also provide the scores for the automatic evaluations type-token ratio and sentiment. Since our model will generate short text segments (tweets cannot be longer than 280 chars), lexical diversity is important. Type-token ratio is a diversity metric to measure the number of unique words to the total words in the generation. We use VADER (Gilbert and Hutto, 2014) to evaluate sentiment, on a range from -1 to 1, with -1 being extremely negative, and 1 being extremely positive. We compare the average sentiments of a user’s generated tweets to the average sentiment of the test set to determine the sentiment error of a given account.

Figure 6: This plot shows the differences in VADER sentiment between accounts in the test set, which makes it a viable measure of style similarity.

Overall, our model performed poorly when compared to the baseline across all metrics. However, as previously stated, the baseline is not able to make a prediction using a single model and takes much longer to train. This is an important consideration because Twitter contains hundreds of millions of accounts, so there is great value in being able to retrain a model on a new account quickly.

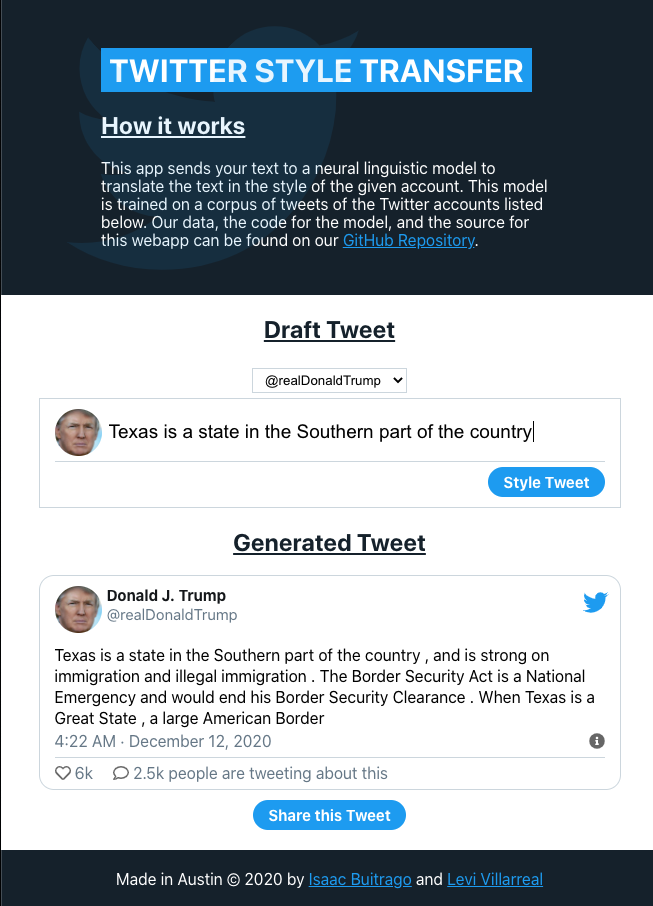

Web Interface

To facilitate accessibility of our work, we present a web interface to allow non-technical users to use our model. This interface is designed to mimic the look and feel of the real Twitter website, to allow for familiarity among those who have used Twitter before. As seen in 8, a user can specify the text they wish to style, and can choose from a dropdown list of accounts what style they wish to emulate. This text and account are used by our pre-trained model, which returns a styled tweet that is presented to the user.

Figure 8: This web application allows for users to specify the text to style, and the account to emulate.

We were able to deploy our application online (Note the first load of the webapp may take up to 30s due to Heroku constraints), although the current version uses an outdated model because the application size limit imposed by our cloud platform, Heroku is 500MB, meaning that after factoring in the size considerations of dependencies, our final pre-trained model exceeds that limit. Future work could include creating a custom web server meant to handle such models and allow for a higher memory limit.

Limitations and Future work

The tweets in figure 7 were generated using greedy decoding, so you can see how words like ”outraged” and ”ignorance” dominate the language of the given account. We attempted to use beam search to improve search error in the decoding step, but this resulted in sub-optimal results as the model sampled out of vocabulary words at each step. Currently the model has two major issues: out of vocabulary words and repeating outputs.

| Account | Tweet 1 | Tweet 2 | Tweet 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| @realDonaldTrump | “ignorance outraged actions <unk>” | “ignorance outraged actions <unk>” | “ignorance outraged actions <unk>” |

| @dril | “outraged natural” | “outraged natural” | “outraged natural” |

| @DalaiLama | “outraged actions kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing” | “outraged actions kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing” | “outraged actions kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing cartoon kissing” |

| @elonmusk | “ignorance outraged actions imaginary pool pool pool pool pool pool pool pool pool pool pool” | “ignorance outraged actions imaginary imaginary imaginary imaginary pool pool pool pool pool pool pool pool” | “ignorance outraged actions imaginary imaginary imaginary imaginary imaginary imaginary imaginary imaginary imaginary pool pool pool” |

Figure 7: Generated tweets for each twitter account

The model is likely sampling out of vocabulary words due to a large vocabulary (5850 words) with a rich morphology (Xie, 2017). Repetitive outputs indicates poor training of the model. Although the training loss for the VAE (4) indicates convergence, it surely has not approximated the global minima of the objective function. One strategy to mitigate this issue is to add an attention matrix to the inputs of the decoder that penalizes repeating text (Xie, 2017).

There are a number of improvements that can be made to improve the quality of generations. Including:

- Decaying network weights

- Anneal learning rate if validation loss does not improve

- Character level generation

- Utilize pre-trained word embeddings on twitter data

- Performing grid search over different learning rates

Also, in order to perform style transfer on input text we need to try concatenating the embeddings of each account to the latent space and utilizing them in the decoding step. We can also try a transformer based architecture to leverage the use of multi-head attention and positional embeddings, which learn the relationship between different words (Dai et al., 2019).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we present a custom Twitter dataset for text style transfer, developed a user interface to facilitate interaction with Natural Language Processing models, and developed a custom text generation model capable of generating tweets specific to a Twitter account. There are further improvements to be made to the model to improve both the quality of generated tweets and perform style transfer on any arbitrary input text.

References

- Oscar Alvarado and Annika Waern. 2018. Towards Algorithmic Experience: Initial Efforts for Social Media Contexts, page 1–12. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA.

- Raad Bin Tareaf. 2017. Tweets Dataset - Top 20 most followed users in Twitter social platform.

- John D. Burger, John Henderson, George Kim, and Guido Zarrella. 2011a. Discriminating gender on Twitter. In Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 1301–1309, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- John D Burger, John Henderson, George Kim, and Guido Zarrella. 2011b. Discriminating gender on twitter. In Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 1301–1309.

- Emily Chen, Kristina Lerman, and Emilio Ferrara. 2020. Tracking social media discourse about the covid-19 pandemic: Development of a public coronavirus twitter data set. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2):e19273.

- Ning Dai, Jianze Liang, Xipeng Qiu, and Xuanjing Huang. 2019. Style transformer: Unpaired text style transfer without disentangled latent representation. CoRR, abs/1905.05621.

- Leon A Gatys, Alexander S Ecker, and Matthias Bethge. 2016. Image style transfer using convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 2414–2423.

- CHE Gilbert and Erric Hutto. 2014. Vader: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. In Eighth International Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (ICWSM-14). Available at (20/04/16) http://comp. social. gatech. edu/papers/icwsm14. vader. hutto. pdf, volume 81, page 82.

- G. E. Hinton, P. Dayan, B. Frey, and R. Neal. 1995. The ”wake-sleep” algorithm for unsupervised neural networks. Science, 268 5214:1158–61.

- Zhiting Hu, Zichao Yang, Xiaodan Liang, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, and Eric P. Xing. 2017. Controllable text generation. CoRR, abs/1703.00955.

- Harsh Jhamtani, Varun Gangal, Eduard Hovy, and Eric Nyberg. 2017. Shakespearizing modern language using copy-enriched sequence-to-sequence models.

- Justin Johnson, Alexandre Alahi, and Li Fei-Fei. 2016. Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. In European Conference on Computer Vision.

- Yoon Kim. 2014. Convolutional neural networks for sentence classification. CoRR, abs/1408.5882.

- Min Kyung Lee, Daniel Kusbit, Anson Kahng, Ji Tae Kim, Xinran Yuan, Allissa Chan, Daniel See, Ritesh Noothigattu, Siheon Lee, Alexandros Psomas, et al. 2019. Webuildai: Participatory framework for algorithmic governance. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW):1–35.

- Stephen Merity, Nitish Shirish Keskar, and Richard Socher. 2017. Regularizing and optimizing lstm language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.02182.

- Aliza Rosen. 2017. Giving you more characters to express yourself.

- Hassan Saif, Miriam Fernandez, Yulan He, and Harith Alani. 2013. Evaluation datasets for twitter sentiment analysis: a survey and a new dataset, the sts-gold.

- Kaz Sato. 2020. Ai gahaku : A masterpiece from your photos.

- Nitish Srivastava, Geoffrey Hinton, Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Ruslan Salakhutdinov. 2014. Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 15(56):1929–1958.

- Alexey Tikhonov, Viacheslav Shibaev, Aleksander Nagaev, Aigul Nugmanova, and Ivan P. Yamshchikov. 2019. Style transfer for texts: Retrain, report errors, compare with rewrites.

- Alexey Tikhonov and Ivan P. Yamshchikov. 2018. What is wrong with style transfer for texts?

- Bo Wang, Adam Tsakalidis, Maria Liakata, Arkaitz Zubiaga, Rob Procter, and Eric Jensen. 2016. Smile twitter emotion dataset.

- Ziang Xie. 2017. Neural text generation: A practical guide. CoRR, abs/1711.09534.

- Jaewon Yang and Jure Leskovec. 2011. Patterns of temporal variation in online media. In Proceedings of the fourth ACM international conference on Web search and data mining, pages 177–186.